Japanese

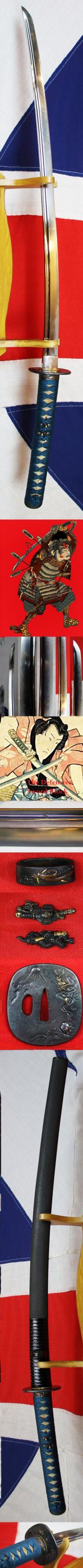

A Stunning, Early, Signed Munemitsu, Bizen School Koto Blade Katana With Hi Circa 1480. A Most Beautiful And Elegant Ancient Samurai Sword By a Master Smith Of the 15th Century

Beautiful, and original, Edo period koshirae {sword mounts and fittings}

The rich mid blue-green torqoise tsuka-ito has just been beautifully restored, as has the black saya, with a ribbed top section, and ishime {stone finish} lacquer to the rest, and as hoped it once again looks absolutely fabulous. A true beauty of an early, signed, samurai art and combat sword, around 550 years old, and a signally fine piece, worthy of any museum grade collection.

Possibly by Bishu Osafune Munemitsu {a smith from the Bunmei reign in the Koto era}

The blade is absolutely beautiful, with hirazukuri, iori-mune, very elegant zori, chu-kissaki and carved with broad and deep hi on both sides, the forging pattern is beautiful, and a gunome-midare of ko-nie, deep ashi, hamon, the tang is original, and full length, and it is mounted with a silver habaki. The blade has a fabulous blocking cut on the mune, a most noble and honourable battle scar that is never removed and kept forever as a sign of the combat blocking move that undoubtedly saved the life of the samurai, and will thus be never removed.

The tsuka has an iron Higo school kashira, a beautiful signed shakudo-nanako fuchi with very fine quality takabori decoration.

Its tsuba is beautiful with a takebori design of Mount Fuji with dragon flying in the sky above, with highlights in gold, silver and copper. The Edo menuki are of a shakudo and gold representation group of samurai armour upon a tachi, and a shakudo and gold dragon {clutching an ancient Ken double edged straight sword with lightning maker} a Edo Antique Ken maki Ryu zu

What with the defensive cut, its shape and form, this fabulous sword has clearly seen combat, yet it is in incredibly beautiful condition for its great age, and it is a joy to behold.

There are many reasons why people enjoy collecting swords. Some people are drawn to the beauty and craftsmanship of swords, while others appreciate their historical and cultural significance. Swords can also be a symbol of power and strength, and some collectors find enjoyment in the challenge of acquiring rare or valuable swords.

One of the greatest joys of sword collecting is the opportunity to learn about the history and culture of different civilisations. Swords have been used by warriors for millennia, and each culture has developed its own unique sword designs and traditions. By studying swords, collectors can gain a deeper understanding of the people who made and used them.

Another joy of sword collecting is the sheer variety of swords that are available. There are swords in our gallery from all over the world and from every period of history. Collectors can choose to specialize in a particular type of sword, such as Japanese katanas or medieval longswords, or they can collect a variety of swords from different cultures and time periods. No matter what your reasons for collecting swords, it is a hobby that can provide many years of enjoyment. Swords are beautiful, fascinating, and historically significant objects.

Every item is accompanied with our unique, Certificate of Authenticity. Of course any certificate of authenticity, given by even the best specialist dealers, in any field, all around the world, is simply a piece of paper,…however, ours is backed up with the fact we are the largest dealers of our kind in the world, with over 100 years and four generation’s of professional trading experience behind us.

The world of antique sword collecting is a fascinating journey into the past, offering a unique lens through which to view history and culture. More than mere weapons, these artifacts serve as tangible connections to the societies and ancient times where they originated. Each blade tells a story, not just of the battles it may have seen but of the craftsmanship, artistic trends, and technological advancement of its time.

The swords mountings can be equally telling. Engravings and decorative elements may enhance the sword’s beauty and hint at its historical context. The materials used for them can reveal the sword’s age

Collecting antique swords, arms and armour is not merely an acquisition of objects; it’s an engagement with the historical and cultural significance that these pieces embody. As collectors, we become custodians of history, preserving these heritage symbols for future generations to study and appreciate.

We are now, likely the oldest, and still thriving, arms armour and militaria stores in the UK, Europe and probably the rest of the world too. We know of no other store of our kind that is still operating under the control its fourth successive generation of family traders

As once told to us by an esteemed regular visitor to us here in our gallery, and the same words that are repeated in his book;

“In these textures lies an extraordinary and unique feature of the sword - the steel itself possesses an intrinsic beauty. The Japanese sword has been appreciated as an art object since its perfection some time during the tenth century AD. Fine swords have been more highly prized than lands or riches, those of superior quality being handed down from generation to generation. In fact, many well-documented swords, whose blades are signed by their makers, survive from nearly a thousand years ago. Recognizable features of the blades of hundreds of schools of sword-making have been punctiliously recorded, and the study of the sword is a guide to the flow of Japanese history.”

Victor Harris

Curator, Assistant Keeper and then Keeper (1998-2003) of the Department of Japanese Antiquities at the British Museum. He studied from 1968-71 under Sato Kenzan, Tokyo National Museum and Society for the Preservation of Japanese Swords read more

6450.00 GBP

A Very Attractive, and Most Rare Original Antique Edo Era Ashigaru {Foot Samurai} Armour and Jingasa Helmet. Commanded in Battle By The Ashigarugashira 足軽頭 . Around 300 Years Old.

17th to 18th century. Its Jingasa helmet is made in hardened leather, decorated with black lacquer, with a large red sun mon, a do cuirass of frontis plate with the same red sun mon, that secures at the back with cords. It has kusari kote arm sleeves and gauntlets, three panels of ito bound kusazuri, this is the plate skirt that protects the lower part of the body as well as the upper leg. It is laced together to the upper plates.

Ashigaru armour was light, flexible and simpler to make than usual samurai armour. It was worn by spear men foot soldiers, in battle or defensive service, and they may be armed with yari or nagananata {polearms}, yumi {bows with arrows} or tanegashima {muskets}, in most samurai armies. It was the most common form of armour in Rokugan.

In the Ōnin War, ashigaru gained a reputation as unruly troops when they looted and burned Miyako (modern-day Kyoto). In the following Sengoku period the aspect of the battle changed from single combat to massed formations. Therefore, ashigaru became the backbone of many feudal armies and some of them rose to greater prominence.

Those who were given control of ashigaru were called ashigarugashira (足軽頭). The most famous of them was Toyotomi Hideyoshi, who also raised many of his warrior followers to samurai status.

Ashigaru formed the backbone of samurai armies in the later periods. The real change for the ashigaru began in 1543 with the introduction of matchlock firearms by the Portuguese. Almost immediately local daimyōs started to equip their ashigaru with the new weapon, which required little training to use proficiently, as compared with the longbow, which took many years to learn. As battles became more complex and forces larger, ashigaru were rigorously trained so that they would hold their ranks in the face of enemy fire.

The advantage of the matchlock guns proved decisive to samurai warfare. This was demonstrated at the Battle of Nagashino in 1575, where carefully positioned ashigaru gunners of the Oda and Tokugawa clans thwarted the Takeda clan's repeated heavy cavalry charges against the Oda clan's defensive lines and broke the back of the Takeda war machine.

After the battle, the ashigaru's role in the armies was cemented as a very powerful complement to the samurai. The advantage was used in the two invasions of Korea in 1592 and 1597 against the Koreans and later the Ming-dynasty Chinese. Though the ratio of guns (matchlocks) to bows was 2:1 during the first invasion, the ratio became 4:1 in the second invasion since the guns proved highly effective

Some samurai would consider wearing ashigaru armour if a mission required them to travel light and fast, such as scouting, and Ronin were also noted for commonly using ashigaru armour, because of it's availability and lesser cost than elaborate armour

Every single item from The Lanes Armoury is accompanied by our unique Certificate of Authenticity. Part of our continued dedication to maintain the standards forged by us over the past 100 years of our family’s trading, as Britain’s oldest established, and favourite, armoury and gallery read more

3895.00 GBP

Superb Early to Mid Edo,Museum Quality Signed Samurai War Helmet Kabuto, by Nobutada, of 21 'Helmet Skull' or 'Bowl Plates', with a Leaping Animal, Carved Wooden and Gold Maedate & Clan Mon of the Sakai Clan, & “Fierce Face” Ressai, Face Armour

A truly fabulous, original, Edo samurai's antique kabuto, war helmet, worthy of a museum display, the best samurai or Japanese art collections, or as a single 'statement' piece for any home. This is, without doubt, one of the most beautiful and fine original antique samurai war helmets, kabuto, we have seen for a jolly long time. Helmets of such beauty and quality as this can be prized and valued as much as a complete original samurai armour.

The imposing beauty of the helmet is entrancing, and the menpo {the moustached, grimacing expression face armour} sets it off superbly with a most intimidating presence. When this was worn by its fierce-some armoured samurai he must have looked spectacularly impressive.

A 21 plate goshozan sujibachi kabuto, with ressei {fierce face } mempo face armour, that has just returned from having the mempo's moustache expertly conserved, and it looks as good as new.

Probably a 17th-18th century, 21 ken plate, Sujibachi, which is a multiple-plate type of Japanese helmet skull bowl with raised ridges or ribs showing where the 21 tate hagi-no-ita (helmet plates) come together creating the main skull bowl bachi, and culminating at the multi stage tehen kanamono finial, with the fukurin metal edges on each of the standing plates.

The mabisashi peak is lacquered and it has a four-tier lacquered iron hineno-jikoro neck-guard laced with gold, and the skull is surmounted by a gilt-lacquered wood leaping animal, the maedate (forecrest), possibly a rabbit or deer, the Fukigaeshi small front wings shows the mon crest symbol of a plain form katabami mon {the wood sorrel flower}.

It's one of popular kamon that is a design of the flower of oxalis corniculata.

The founder of the clan that chose this flower as their mon had wished that their descendants would flourish well. Because oxalis corniculata is renown, and fertile plant.

the mon form as used by clans such as the Sakai, including daimyo lord Sakai Tadayo

One of the great Sakai clan lords was Sakai Tadayo (酒井 忠世, July 14, 1572 – April 24, 1636). He was a Japanese daimyō of the Sengoku period, and high-ranking government advisor, holding the title of Rōjū, and later Tairō. You can see his image in the gallery wearing the very same form of war helmet kabuto.

The son of Sakai Shigetada, Tadayo was born in Nishio, Mikawa Province; his childhood name was Manchiyo. He became a trusted elder (rōjū) in Toyotomi Hideyoshi's government, alongside Tokugawa Ieyasu. Under Hideyoshi, he was made lord of Kawagoe Castle (in Musashi Province, today Saitama Prefecture) and later of Nagoya Castle in Kyūshū's Hizen Province. In 1600, in the lead-up to the decisive Sekigahara campaign, he fought against the Tokugawa at Aizu, and submitted to them at the siege of Ueda. Thus, having joined the Tokugawa prior to the battle of Sekigahara itself, Sakai was made a fudai daimyō, and counted among the Tokugawa's more trusted retainers. He served under Ieyasu for a time, and under the second shōgun, Tokugawa Hidetada, as a hatamoto.

The lacquered iron menpo (face mask) with four-lame yodarekake face armour. The kabuto is signed on the interior Nobutada saku Nobutada made this

After the introduction of firearms, smoke blanketed many battlefields, causing confusion for the troops. So they could be more readily identified, samurai began to wear helmets with elaborate ornaments at the front, back, or sides, often featuring an intricate crest (maedate).

In their quest for unique and meaningful armour, samurai turned to nature, folklore, or religion for inspiration. Whatever the source, they selected designs for their armor that would set them apart and communicate their personality and beliefs, whether whimsical, frightening, or spiritual.

An antique woodblock print in the gallery, likely of Sakai Tadayo, showing his same form of war helmet kabuto, decorated with his same Sakai clan mon of the katabami, and he also has a leaping animal, gold covered carved wood, as his maedate helmet crest as has ours. And he has the same 'fierce face' mempo face armour with the very same style of elaborate, pronounced moustache.

The Fukigaeshi on the left facing side of the helmet shows the mon crest symbol of a plain katabami mon but small surface lacquer area partly missing. There are very small age nicks to the helmet lacquer. It has its original helmet lining but most removed back to reveal the signature

Every single item from The Lanes Armoury is accompanied by our unique Certificate of Authenticity. Part of our continued dedication to maintain the standards forged by us over the past 100 years of our family’s trading, as Britain’s oldest established, and favourite, armoury and gallery read more

7950.00 GBP

Beautiful Koto, Samurai's Paired Swords Daisho, 425-525 Years Old. Katana and Chisa Katana. Edo Period Koshirae, Ume 'Maeda' 前田氏 Clan Mon Tsubas, 'Pine Needle' & Urushi Lacquer Sayas. The Maeda Clan, Lords of Kaga, One of the Most Powerful in Japan

The daisho’s blades, are both late Koto era, likely made between 1500 to 1600. They are most beautiful Koto period blades, of much elegance, one with its gently undulating notare hamon, the other its suguha hamon.

Both swords have gold and shakudo fushi kashira, one with the handachi form, with kabuto-gane pommel, decorated with gold lines on a nanako ground, the other with a fuchi that has a takebori dragon on a nanako ground, and the kashira is polished carved buffalo horn.

Mounted with a superb, Edo period, original pair of iron round plate sukashi daisho tsuba, with pierced Maeda clan mon of the ume, plum blossom, within both the daito and shoto tsuba. Pierced with the plum blossom mon pattern {with twigs}. used by the samurai connected and serving with the Maeda clan.The Maeda clan (前田氏, Maeda-shi) was a Japanese samurai clan who occupied most of the Hokuriku region of central Honshū from the end of the Sengoku period through the Meiji Restoration of 1868. The Maeda claimed descent from the Sugawara clan through Sugawara no Kiyotomo and Sugawara no Michizane in the eighth and ninth centuries; however, the line of descent is uncertain. The Maeda rose to prominence as daimyō of Kaga Domain under the Edo period Tokugawa shogunate, which was second only to the Tokugawa clan in kokudaka (land value).

The daisho's tsuba are likely from the Umetada tsuba school of tsuba craftsman, Umetada were the foremost swordsmiths of their day. Their 18th Master, Shigeyoshi I, is said to have made sword-furniture for the Ashikaga Shōgun (end of 14th century), but none of his work is known. Serious study of Umetada sword guards {tsuba} begins with the 25th Master, Miōju, or Shigeyoshi II; {b.1558; d. 1631}. His headquarters, as also those of the succeeding nine Masters, were at Kiōto, but he was invited to several provincial centres and exerted a lasting influence on the local schools.

A branch founded by Naritsugu (c. 1752) worked at Yedo, while various members of the family were active at other centres. The Umetada style in general is a skilful combination of chiselling and incrustation or inlay.

The daisho’s matching sayas are stunning, both with a highly complex decorative design pattern of pine needles laid upon black urushi lacquer, in a seemingly random pattern. But, in reality each pine needle was strategically placed upon them, when creating the decorative finish, with just a single needle, and just one at a time, to give the impression they fell naturally upon the ground from above, from a pine tree. The surface was then lacquered in clear transparent urushi lacquer to create a uniform smooth surface. in the Edo period it would take anything around a year or more to create a samurai sword saya, as the urushi lacquer coating would be anything up to 12 coats deep, and each would take a month to dry as they were made using on natural materials, not modern quick drying synthetic cellulose lacquers as used today.

The samurai's daisho, {his two swords title when carried within his obi} was named as such when his swords were worn together, and it describes the combination of the samurai’s daito and shoto {long mounted sword, and short mounted sword}. In the earlier period of the samurai, a daisho were comprising the matching of his long tachi and much shorter tanto, but in the later period, much more often, it was the matching of a combination of a katana and a wakazashi. However, some samurai may choose an alternative coupling of a katana matched with an o-wakazashi or chisa katana, or, even two chisa katana, but one sword was more usually mounted shorter than the other, despite the blades being of near equal length. This particular daisho that we offer here, is the combination of the latter type, that was specifically advantageous for a samurai trained, as was the famous samurai, Musashi, using a twin-sword combat method, of a sword carried and used together in each hand, simultaneously. For Musashi, this was a combat style that was undefeatable, when combined with his incredible skill.

Using a daisho of near equal length blades was the art of twin sword combat, using two at once in unison, one in each hand, the form as previously mentioned as used by the great and legendary samurai, Miyamoto Musashi, who reportedly killed 60 men before his 30th birthday.

Miyamoto Musashi 1584 – June 13, 1645), also known as Shinmen Takezo, Miyamoto Bennosuke or, by his Buddhist name, Niten Doraku, was an expert Japanese swordsman and ronin. Musashi, as he was often simply known, became renowned through stories of his excellent, and unique double bladed swordsmanship and undefeated record in his 60 duels. He was the founder of the Hyoho Niten Ichi-ryu or Niten-ryu style of swordsmanship and in his final years authored the The Book of Five Rings, a book on strategy, tactics, and philosophy that is still studied today.

Tsuba were made by whole dynasties of craftsmen whose only craft was making tsuba. They were usually lavishly decorated. In addition to being collectors items, they were often used as heirlooms, passed from one generation to the next. Japanese families with samurai roots sometimes have their family crest (mon) crafted onto a tsuba. Tsuba can be found in a variety of metals and alloys, including iron, steel, brass, copper and shakudo. In a duel, two participants may lock their katana together at the point of the tsuba and push, trying to gain a better position from which to strike the other down. This is known as tsubazeriai pushing tsuba against each other. A samurai's daisho were his swords, as worn together, as stated in the Tokugawa edicts. In a samurai family the swords were so revered that they were passed down from generation to generation, from father to son. If the hilt or scabbard wore out or broke, new ones would be fashioned for the all-important blade. The hilt, the tsuba (hand guard), and the scabbard themselves were often great art objects, with fittings sometimes of gold or silver. Often, too, they told a story from Japanese myths. Magnificent specimens of Japanese swords can be seen today in the Tokugawa Art Museum’s collection in Nagoya, Japan.

In creating the sword, a sword craftsman, such as, say, the legendary Masamune, had to surmount a virtual technological impossibility. The blade had to be forged so that it would hold a very sharp edge and yet not break in the ferocity of a duel. To achieve these twin objectives, the sword maker was faced with a considerable metallurgical challenge. Steel that is hard enough to take a sharp edge is brittle. Conversely, steel that will not break is considered soft steel and will not take a keen edge. Japanese sword artisans solved that dilemma in an ingenious way. Four metal bars a soft iron bar to guard against the blade breaking, two hard iron bars to prevent bending and a steel bar to take a sharp cutting edge were all heated at a high temperature, then hammered together into a long, rectangular bar that would become the sword blade. When the swordsmith worked the blade to shape it, the steel took the beginnings of an edge, while the softer metal ensured the blade would not break. This intricate forging process was followed by numerous complex processes culminating in specialist polishing to reveal the blades hamon and to thus create the blade's sharp edge. Inazo Nitobe stated: The swordsmith was not a mere artisan but an inspired artist and his workshop a sanctuary. Daily, he commenced his craft with prayer and purification, or, as the phrase was, the committed his soul and spirit into the forging and tempering of the steel.

Celebrated sword masters in the golden age of the samurai, roughly from the 13th to the 17th centuries, were indeed revered to the status they richly deserved.

Daito sword blade length tsuba to tip 24,5 inches, overall 36.5 inches long in its saya.

Shoto sword blade length tsuba to tip 24.25,

overall 34 inches long in its saya.

As once told to us by an esteemed regular visitor to us here in our gallery, and the same words that are repeated in his book;

“In these textures lies an extraordinary and unique feature of the sword - the steel itself possesses an intrinsic beauty. The Japanese sword has been appreciated as an art object since its perfection some time during the tenth century AD. Fine swords have been more highly prized than lands or riches, those of superior quality being handed down from generation to generation. In fact, many well-documented swords, whose blades are signed by their makers, survive from nearly a thousand years ago. Recognizable features of the blades of hundreds of schools of sword-making have been punctiliously recorded, and the study of the sword is a guide to the flow of Japanese history.”

Victor Harris

Curator, Assistant Keeper and then Keeper (1998-2003) of the Department of Japanese Antiquities at the British Museum. He studied from 1968-71 under Sato Kenzan, Tokyo National Museum and Society for the Preservation of Japanese Swords

Every single item from The Lanes Armoury is accompanied by our unique Certificate of Authenticity. Part of our continued dedication to maintain the standards forged by us over the past 100 years of our family’s trading, as Britain’s oldest established, and favourite, armoury and gallery read more

16500.00 GBP

A Beautiful Katana, Signed, Bizen Yokoyama Sukekane 尉祐包 Dated February 1867, He Was The 13th Generation Sukesada & 58th Generation From The Founder of Bizen Smiths In Superb Polish With Edo Period Mounts of Shakudo & Gold by Yasuyuki 安随

Signed, 備陽長船住横山俊左衛門尉祐包

Biyo {Bishu} Osafune Jyu Yokoyama Shunzaemon Jo Sukekane

備陽長船住 is where he lives and 横山俊左衛門尉祐包 is his full name.

The 13th generation of Sukesada, who worked from 1835 to 1872, and this sword was made in the 3rd year of Keio, so it was made in February 1867.

The third says that he is the 58th grandson of the founder of Bizen smithing, Bizen Tomonari. It also shows the date of creation. Blades of the 19th-century Yokoyama school frequently declared their lineage as being directly descended from the 13th-century smith Tomonari.

It has a stunning urushi lacquered original Edo saya with ribbing on the black urushi middle top section, and crushed abilone, over green, black and clear urushi lacquer, on the top and bottom sections a most pleasing and artistic combination.

Original Edo shakudo fuchi kashira decorated with silver and gold birds, bamboo and flowers, on a hammered ground, signed Yasuyuki 安随. The tettsu tsuba has a geometric openwork design of an approaching wagon wheel with hon-zogan decoration of shinchu hira inlay. The tsuka ito {silk binding} is blue-green

A pair of superb menuki, in gold and shakudo, one is the turtle the other the phoenix. In Japanese folklore, the minogame, it is a legendary turtle of tremendous age. Sometimes living for up to 10,000 years, its most distinctive feature is the tail of seaweed and algae that trails behind it.

The most well known minogame {turtle} in Japan comes from the tale of Urashima Tarō, a legendary fisherman who rescues a turtle being tormented by children on a beach. A minogame informs him that he has actually rescued the daughter of the sea god Ryūjin, and takes him down to the bottom of the ocean to receive his thanks.

The other menuki is a Hō-ō bird . As the herald of a new age, the Hō-ō {phoenix} decends from heaven to earth to do good deeds, and then it returns to its celestial abode to await a new era. It is both a symbol of peace (when the bird appears) and a symbol of disharmony (when the bird disappears).

Some provinces of Japan were famous for their contribution to the ishime style of urushi lacquer art: the province of Edo (later Tokyo), for example, produced the most beautiful lacquered pieces from the 17th to the 18th centuries. Lords and shoguns privately employed lacquerers to produce ceremonial and decorative objects for their homes and palaces.

The varnish used in Japanese lacquer is made from the sap of the urushi tree, also known as the lacquer tree or the Japanese varnish tree (Rhus vernacifera), which mainly grows in Japan and China, as well as Southeast Asia. Japanese lacquer, 漆 urushi, is made from the sap of the lacquer tree. The tree must be tapped carefully, as in its raw form the liquid is poisonous to the touch, and even breathing in the fumes can be dangerous. But people in Japan have been working with this material for many millennia, so there has been time to refine the technique!

Flowing from incisions made in the bark, the sap, or raw lacquer is a viscous greyish-white juice. The harvesting of the resin can only be done in very small quantities.

Three to five years after being harvested, the resin is treated to make an extremely resistant, honey-textured lacquer. After filtering, homogenization and dehydration, the sap becomes transparent and can be tinted in black, red, yellow, green or brown.

Once applied on an object, lacquer is dried under very precise conditions: a temperature between 25 and 30°C and a humidity level between 75 and 80%. Its harvesting and highly technical processing make urushi an expensive raw material applied in exceptionally fine successive layers, on objects such as bowls or boxes, or as you see, samurai sword saya {scabbards}. After heating and filtering, urushi can be applied directly to a solid, usually wooden, base. Pure urushi dries into a transparent film, while the more familiar black and red colours are created by adding minerals to the material. Each layer is left to dry and polished before the next layer is added. This process can be very time-consuming and labour-intensive, which contributes to the desirability, and high costs, of traditionally made lacquer goods. The skills and techniques of Japanese lacquer have been passed down through the generations for many centuries. For four hundred years, the master artisans of Zohiko’s Kyoto workshop have provided refined lacquer articles for the imperial household. It is extraordinary that a finest urushi lacquer saya would have taken up to, and over, a year to hand produce, by some of the most finely skilled artisans in the world.

Shakudo {that can be used to make samurai sword mounts and fittings} is a billon of gold and copper (typically 4-10% gold, 96-90% copper) which can be treated to form an indigo/black patina resembling lacquer. Unpatinated shakudo Visually resembles bronze; the dark colour is induced by applying and heating rokusho, a special patination formula.

Shakudo was historically used in Japan to construct or decorate the finest katana fittings such as fuchi-kashira, tsuba, menuki, and kozuka; as well as other small ornaments. When it was introduced to the West in the mid-19th century, it was thought to be previously unknown outside Asia, but recent studies have suggested close similarities to certain decorative alloys used in ancient Egypt, Greece, and Rome.

The British Museum has a small tanto signed by the same smith Bishu Osafune Ju Yokoyama Sukekane’

https://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O90821/dagger-and-scabbard-sukekane/

Sukekane was the 13th mainline master of the Bizen Yokoyama school, which was founded in the later 16th century by Yosozaemon no Jo Sukesada. It is said that Sukesada relocated to the nearby village of Yokoyama after the great flooding of Osafune at this time. Sukesada’s great-grandson, Sanzaemon no

Jo Sukesada, whose personal name was Toshiro and was the 4th generation, was the first representative of the school to work in shinto times.

All these smiths were named Sukesada and as they entered the shinshinto period, although they retained the character “Suke” in their names, many used a different second character instead of “Sada”. However, although living and signing their work

with Yokoyama, they appreciated that their spiritual and cultural home was still Osafune, by including this in their mei.

This is the first of two generations named Sukekane and he died in 1872, a few years after making this blade. He was taught swordmaking by one Sukenaga who was actually from a corollary family to the mainline of Yokoyama smiths. Sukenaga also signed on his nakago that he was the 56th generation descended from Tomonari. Sukenaga’s brother, Sukemori, was adopted into the mainline school, as the 12th master and Sukekane, his natural son, became the 13th master. read more

6450.00 GBP

A Delightful & Beautiful Early to Mid Edo Period 1598-1863 Samurai War Arrow. A Tagari-Ya Of Yadake Bamboo, With Sea Eagle Flights and Traditional Tamagahane Steel Head In Incredibly Rare Stunningly Beautiful Polish

It is most rare to find original, antique samurai war arrows {ya} that still have beautifully polished tamagahane steel blades, that they would all have had originally, that often show the traditional hamon, the same as a traditional samurai sword would have had.

Acquired by us by personally being permitted to select from the private collection one of the world's greatest, highly respected and renown archery, bow and arrow experts. Who had spent his life travelling the world to lecture on archery and to accumulate the finest arrows and bows he could find. .

With original traditional eagle feathers, probably the large edge-wing feathers of a Japanese sea eagle. The armour piercing arrow tip, that is swollen at the tip to have the extra piercing power to penetrate armour and helmets {kabuto}, is a brightly polished, traditional tamagahane steel hand made, by a sword smith, long arrow head, originally hand made with folding and tempering exactly as would be a samurai sword blade, possibly signed on the tang under the binding but we would never remove it to see. The Edo period early eagle feathers are now slightly worn. It is entirely indicative of the Japanese principle that as much time skill and effort be used to create a single 'fire and forget' arrow, as would be used to make a tanto or katana. A British or European blacksmith might once have made ten or twenty arrows a day, a Japanese craftsman might take a week to make a single arrow, that has a useable combat life of maybe two minutes, the same as a simplest British long bow arrow.

The Togari-Ya or pointed arrowheads look like a small Yari (spear) were pointed arrowheads were used only for war and are armour piercing arrows . Despite being somewhat of a weapon that was 'fire and forget' it was created regardless of cost and time, like no other arrow ever was outside of Japan. For example, to create the arrow head alone, in the very same traditional way today, using tamahagane steel, folding and forging, water quench tempering, then followed by polishing, it would likely cost way in excess of a thousand pounds, that is if you could find a Japanese master sword smith today who would make one for you. Then would would need hafting, binding, and feathering, by a completely separate artisan, and finally, using eagle feathers as flights, would be very likely impossible. This is a simple example of how incredible value finest samurai weaponry can be, items that can be acquired from us that would cost many times the price of our original antiques in order to recreate today. Kyu Jutsu is the art of Japanese archery.The beginning of archery in Japan is pre-historical. The first images picturing the distinct Japanese asymmetrical longbow are from the Yayoi period (c. 500 BC – 300 AD).

The changing of society and the military class (samurai) taking power at the end of the first millennium created a requirement for education in archery. This led to the birth of the first kyujutsu ryūha (style), the Henmi-ryū, founded by Henmi Kiyomitsu in the 12th century. The Takeda-ryū and the mounted archery school Ogasawara-ryū were later founded by his descendants. The need for archers grew dramatically during the Genpei War (1180–1185) and as a result the founder of the Ogasawara-ryū (Ogasawara Nagakiyo), began teaching yabusame (mounted archery) In the twelfth and thirteenth century a bow was the primary weapon of a warrior on the battlefield. Bow on the battlefield stopped dominating only after the appearance of firearm.The beginning of archery in Japan is pre-historical. The first images picturing the distinct Japanese asymmetrical longbow are from the Yayoi period (c. 500 BC – 300 AD).

The changing of society and the military class (samurai) taking power at the end of the first millennium created a requirement for education in archery. This led to the birth of the first kyujutsu ryūha (style), the Henmi-ryū, founded by Henmi Kiyomitsu in the 12th century. The Takeda-ryū and the mounted archery school Ogasawara-ryū were later founded by his descendants. The need for archers grew dramatically during the Genpei War (1180–1185) and as a result the founder of the Ogasawara-ryū (Ogasawara Nagakiyo), began teaching yabusame (mounted archery) Warriors practiced several types of archery, according to changes in weaponry and the role of the military in different periods. Mounted archery, also known as military archery, was the most prized of warrior skills and was practiced consistently by professional soldiers from the outset in Japan. Different procedures were followed that distinguished archery intended as warrior training from contests or religious practices in which form and formality were of primary importance. Civil archery entailed shooting from a standing position, and emphasis was placed upon form rather than meeting a target accurately. By far the most common type of archery in Japan, civil or civilian archery contests did not provide sufficient preparation for battle, and remained largely ceremonial. By contrast, military training entailed mounted maneuvers in which infantry troops with bow and arrow supported equestrian archers.

Mock battles were staged, sometimes as a show of force to dissuade enemy forces from attacking. While early medieval warfare often began with a formalized archery contest between commanders, deployment of firearms and the constant warfare of the 15th and 16th centuries ultimately led to the decline of archery in battle. In the Edo period archery was considered an art, and members of the warrior classes participated in archery contests that venerated this technique as the most favoured weapon of the samurai. In the gallery is from an Edo exhibition of archery that shows a tagari ya arrow pierced completely through, back and front, an armoured steel multi plate kabuto helmet. Another photo shows an unmounted arrow head with the considerable length of the tang that is concealed by the haft.

Every item is accompanied with our unique, Certificate of Authenticity. Of course any certificate of authenticity, given by even the best specialist dealers, in any field, all around the world, is simply a piece of paper,…however, ours is backed up with the fact we are the largest dealers of our kind in the world, with over 100 years and four generation’s of professional trading experience behind us read more

645.00 GBP

A Superb Antique, Shinto Era, Unokubi (鵜首) Zukuri Blade Tantō, 17th Century. Edo Matsushiro Sinano School Sinchu and Silver Koshirae. Just Arrived From A Premium Grade Collection, Previously Acquired Over Decades

A beautiful little tanto with a fine Shinto blade of rare blade shape, in very clean polish, with just a very few minuscule age surface marks which is remarkable as it is around 400 years old. The tsuka {hilt} is very unusually bound in its original, Edo period, leather tsuka-ito in partial battle-wrap style over traditional white samegawa {giant rayskin}. The saya has stunning and intricately applied pine needle decor beneath clear lacquer and overall this early samurai dagger is incredibly appealing, and would make a fine start to a collection, or a great addition to an already existing one. The superb samurai swords that just arrived {including this one} are numbering around 25 fine pieces, from the Koto to Shinshinto period vary from tachi to katana, chisa katana, wakazashi and tanto And include, two, very fine signed ancestral bladed WW2 mounted officer's swords. One in such fine condition one could imagine it was just surrendered last week, by a Japanese colonel, not 80 years ago!

Unokubi (鵜首) is an uncommon tantō style akin to the kanmuri-otoshi, with a back that grows abruptly thinner around the middle of the blade; however, the unokubi zukuri regains its thickness just before the point. There is normally a short, wide groove {hi} extending to the midway point on the blade, this is a most unusual form of unokubi zukuri blade tanto without a hi.

The fuchigashira and sayagaki and jiri are all matching brass decorated with fulsome designs and silver striping. Fully matching suite of sinchu and contrasting silver line mounts to the tsuka and saya, all from the Edo period Matsushiro Sinano school.

The tanto was invented partway through the Heian period. With the beginning of the Kamakura period, tanto were forged to be more aesthetically pleasing, and hira and uchi-sori tanto becoming the most popular styles. Near the middle of the Kamakura period, more tant? artisans were seen, increasing the abundance of the weapon, and the kanmuri-otoshi style became prevalent in the cities of Kyoto and Yamato. Because of the style introduced by the tachi in the late Kamakura period, tanto began to be forged longer and wider. The introduction of the Hachiman faith became visible in the carvings in the hilts around this time. The hamon (line of temper) is similar to that of the tachi, except for the absence of choji-midare, which is nioi and utsuri. Gunomi-midare and suguha are found to have taken its place.

During the era of the Northern and Southern Courts, the tanto were forged to be up to forty centimetres as opposed to the normal one shaku (about thirty centimetres) length. The blades became thinner between the uri and the omote, and wider between the ha and mune. At this point in time, two styles of hamon were prevalent: the older style, which was subtle and artistic, and the newer, more popular style. With the beginning of the Muromachi period, constant fighting caused the greater production of blades. Blades that were custom-forged still were of exceptional quality. As the end of the period neared, the average blade narrowed and the curvature shallowed

Blade length 7 1/2 inches long tsuba to tip, overall in saya 12 3/4 inches

It will come complete, with our compliments, with a transparent display stand {not the antique one in the photos} a most decorative damask storage bag, a pair of white handling gloves and a white microfibre cleaning cloth. read more

3250.00 GBP

A Beautiful, Signed (山城守藤原秀辰) Hidetoki, Shinto Chisa Katana With Exceptional, Original Edo Period, Nashiji Gold & Contrasting Brown and Red Ground Urushi Lacquer Saya, Decorated With Representations of Longevity, Strength, Loyalty, & Good Fortune

A katana signed Hidetoki (山城守秀辰) a respected swordsmith from the Seki (Tokuin school), with several generations known, particularly the second-generation Hidetoki from the Early Edo period (Shōhō era, 1644–1648), known for producing sharp, highly-rated blades (Wazamono). These signatures often appear as "Seki-jū Yamashiro no Kami Fujiwara Hidetoki" (関住山城守藤原秀辰) for the first generation, and later as just "Yamashiro no Kami Hidetoki" by the second generation.

The katana is mounted in superb original Edo koshirae, with a Higo school iron kashira, and a tetsu fuchi, made in two slotted together parts, with a brass rimmed inner liner. Also, including a pair of shakudo menuki of dragons wrapped beneath beautiful, blue, tsuka-ito. A superb round tetsu tsuba with gold and copper filled kodzukana. With {two holes} udenuki no ana for the tying of an udenuki no O {wrist cord} that is done in a specific way, that requires these two holes in a specific position. It should be fastened/looped (called shirushizuke) on the fuchi part of the sword (the metal bordering piece between the swords tsuba (guard) and the tsuka (handle). Ideally, for both short and long swords- they should be the same length. It stops the samurai from dropping their katana during combat

It further assists the samurai in holding the strap in his mouth when dismounting or mounting a horse)

The original Edo saya of the sword is utterly amazing, it is decorated in dark brown and mid red urushi lacquer to simulate the bark of the pine tree with tiny speckles of abilone shell representing minuscule snow flakes, above that decor ground are nishiji lacquer pine-cones with their elongated bunched fascicle which are actually pine tree leaves, but physically, more greatly resemble elongated needles. The quality of the craftsmanship to create such a desgn is breathtaking.

In the gallery is a powerful Japanese woodblock print attributed to Tsukioka Yoshitoshi (1839–1892), from the 100 Aspects of the Moon series (1885–1892).

It depicts a samurai with his attendant beneath a pine tree, gazing toward a moonlit sky, embodying Yoshitoshi’s fascination with loyalty and reflection.

Japanese decor featuring pine cones often highlight the tree's symbolism of longevity and resilience, appearing in traditional kacho-ga (bird-and-flower) art by masters like Kono Bairei (1844–1895)

Pine (Matsu): Represents longevity, strength, and good fortune, often used in New Year's decorations and art for its evergreen nature.

Pine Cones: A specific symbol of fertility and the continuation of life, beautifully complementing the pine's overall meaning.

The chisa katana was able to be used with one or two hands like a katana (with a small gap in between the hands) and especially made for double sword combat a sword in each hand. It was the weapon of preference worn by the personal Samurai guard of a Daimyo Samurai war lord clan chief, as very often the Daimyo would be often likely within his castle than without. The chisa katana sword was far more effective as a defence against any threat to the Daimyo's life by assassins or the so-called Ninja when hand to hand sword combat was within the castle structure, due to the restrictions of their uniform low ceiling height. But in trained hands this sword would have been a formidable weapon in close combat conditions, when the assassins were at their most dangerous. The hilt was usually around ten to eleven inches in length, but could be from eight inches or up to twelve inches depending on the Samurai's preference. Chisa katana, Chiisagatana or literally "short katana", are shoto mounted as katana. It is fair to say wakizashi are shoto which are mounted in a similar way to katana, but in this instance we are considering the predecessors of the daisho. In the transitional period from tachi to katana, katana were called "uchigatana", and shoto were referred to as "koshigatana" and "chiisagatana", in many cases quite longer than the later more normal length wakizashi.

There are many reasons why people enjoy collecting swords. Some people are drawn to the beauty and craftsmanship of swords, while others appreciate their historical and cultural significance. Swords can also be a symbol of power and strength, and some collectors find enjoyment in the challenge of acquiring rare or valuable swords.

One of the greatest joys of sword collecting is the opportunity to learn about the history and culture of different civilisations. Swords have been used by warriors for millennia, and each culture has developed its own unique sword designs and traditions. By studying swords, collectors can gain a deeper understanding of the people who made and used them.

Another joy of sword collecting is the sheer variety of swords that are available. There are swords in our gallery from all over the world and from every period of history. Collectors can choose to specialize in a particular type of sword, such as Japanese katanas or medieval longswords, or they can collect a variety of swords from different cultures and time periods. No matter what your reasons for collecting swords, it is a hobby that can provide many years of enjoyment. Swords are beautiful, fascinating, and historically significant objects.

Every item is accompanied with our unique, Certificate of Authenticity. Of course any certificate of authenticity, given by even the best specialist dealers, in any field, all around the world, is simply a piece of paper,…however, ours is backed up with the fact we are the largest dealers of our kind in the world, with over 100 years and four generation’s of professional trading experience behind us.

The world of antique sword collecting is a fascinating journey into the past, offering a unique lens through which to view history and culture. More than mere weapons, these artifacts serve as tangible connections to the societies and ancient times where they originated. Each blade tells a story, not just of the battles it may have seen but of the craftsmanship, artistic trends, and technological advancement of its time.

The swords mountings can be equally telling. Engravings and decorative elements may enhance the sword’s beauty and hint at its historical context. The materials used for them can reveal the sword’s age

Collecting antique swords, arms and armour is not merely an acquisition of objects; it’s an engagement with the historical and cultural significance that these pieces embody. As collectors, we become custodians of history, preserving these heritage symbols for future generations to study and appreciate.

We are now, likely the oldest, and still thriving, arms armour and militaria stores in the UK, Europe and probably the rest of the world too. We know of no other store of our kind that is still operating under the control its fourth successive generation of family traders

As once told to us by an esteemed regular visitor to us here in our gallery, and the same words that are repeated in his book;

“In these textures lies an extraordinary and unique feature of the sword - the steel itself possesses an intrinsic beauty. The Japanese sword has been appreciated as an art object since its perfection some time during the tenth century AD. Fine swords have been more highly prized than lands or riches, those of superior quality being handed down from generation to generation. In fact, many well-documented swords, whose blades are signed by their makers, survive from nearly a thousand years ago. Recognizable features of the blades of hundreds of schools of sword-making have been punctiliously recorded, and the study of the sword is a guide to the flow of Japanese history.”

Victor Harris

Curator, Assistant Keeper and then Keeper (1998-2003) of the Department of Japanese Antiquities at the British Museum. He studied from 1968-71 under Sato Kenzan, Tokyo National Museum and Society for the Preservation of Japanese Swords read more

6450.00 GBP

A Beautiful Koto Period Samurai Chisa Katana, Around 500 Years Old With All Original Edo Period Fine Quality fittings

Most handsome original Koto period samurai sword with fine quality original matching Edo period fuchigashira and menuki with gold decorated flowers and birds, beautiful, iron, shin no maru-gata tsuba 18th Century

Original Edo urushi lacquered saya in black

A katana was two shaku or longer in length (one shaku = about 11.93 inches). However, the Chisa katana is longer than the wakizashi, which was somewhere in between one and two shaku in length. The most common blade lengths for Chisa katana was approximately eighteen to twenty-four inches. They were most commonly made in the Buke-Zukuri mounting (which is generally what is seen on katana and wakizashi). The chisa katana was able to be used with one or even two hands like a katana. The Chisa Katana is a slightly shorter Katana highly suitable for two handed, or two sword combat, or, combat within enclosed areas such as castles or buildings. As such they were often the sword of choice for the personal Samurai guard of a Daimyo, and generally the only warriors permitted to be armed in his presence. Chisa katana, Chiisagatana or literally "short katana", are shoto mounted as katana.

The chisa katana was also the long sword of choice for the art of twin sword combat, using two at once in unison, a chisa katana and wakazashi, one in each hand, a form used by the great and legendary samurai Miyamoto Musashi who reportedly killed 60 men before his 30th birthday.

Miyamoto Musashi 1584 – June 13, 1645), also known as Shinmen Takezo, Miyamoto Bennosuke or, by his Buddhist name, Niten Doraku, was an expert Japanese swordsman and ronin. Musashi, as he was often simply known, became renowned through stories of his excellent, and unique double bladed swordsmanship and undefeated record in his 60 duels. He was the founder of the Hyoho Niten Ichi-ryu or Niten-ryu style of swordsmanship and in his final years authored the The Book of Five Rings, a book on strategy, tactics, and philosophy that is still studied today.

“In these textures lies an extraordinary and unique feature of the sword - the steel itself possesses an intrinsic beauty. The Japanese sword has been appreciated as an art object since its perfection some time during the tenth century AD. Fine swords have been more highly prized than lands or riches, those of superior quality being handed down from generation to generation. In fact, many well-documented swords, whose blades are signed by their makers, survive from nearly a thousand years ago. Recognizable features of the blades of hundreds of schools of sword-making have been punctiliously recorded, and the study of the sword is a guide to the flow of Japanese history.”

As once told to us by Victor Harris who, as an esteemed regular visitor to us here in our gallery, quoted the same words above, that are repeated in his book.

Victor Harris

Curator, Assistant Keeper and then Keeper (1998-2003) of the Department of Japanese Antiquities at the British Museum. He studied from 1968-71 under Sato Kenzan, Tokyo National Museum and Society for the Preservation of Japanese Swords

21 inch blade tsuba to tip. 32 inches long overall

Every single item from The Lanes Armoury is accompanied by our unique Certificate of Authenticity. Part of our continued dedication to maintain the standards forged by us over the past 100 years of our family’s trading, as Britain’s oldest established, and favourite, armoury and gallery read more

4995.00 GBP

A Very Beautiful & Incredibly Elegant Koto Katana Art Sword Circa 1500, With Very Fine All Original Edo Koshirae, of Finely Decorated Shakudo, Combined With Exceptional Urushi Lacquer Work. Kashira Decorated with ‘The Monkey Reaching for the Moon’

Very fine original Edo period fittings, mokko gata tsuba and saya. Shakudo fuchi-kashira, decorated with a wonderfully defined little long armed monkey reaching for the moon's reflection in a stream. The long armed monkey is on the kashira, the stream is represented on the fuchi. ‘The Monkey Reaching for the Moon’, fuchi-kashira, depicts a delightful little monkey hanging from a tree branch over the surface of water, reaching down to touch the reflection of the moon. This imagery is undoubtedly derived from a popular Buddhist story that warns how the spiritually unenlightened cannot distinguish between reality and illusion. We very rarely get swords with fittings decorated with the fable of 'the monkey reaching for the moon', but by most unusual good fortune, we have had two this month.

Shakudo and gold menuki of artistically bound reeds, with a fine mokko-shaped Higo school iron tsuba with a raised mimi {edge}, and a black beautiful ishime urushi lacquered saya with matching copper ishime koiguchi, kurikata and kojiri, {scabbard mountings}.

It has a very beautiful 25.25 inch blade, measured tsuba to tip, Typical Koto style and period, an extremely elegant blade with fine graduation, beautiful curvature and iconic Koto form small kissaki It has a superb complex hamon of a choji and crab-claw pattern.

Some provinces of Japan were famous for their contribution to the ishime style of urushi lacquer art: the province of Edo (later Tokyo), for example, produced the most beautiful lacquered pieces from the 17th to the 18th centuries. Lords and shoguns privately employed lacquerers to produce ceremonial and decorative objects for their homes and palaces.

The varnish used in Japanese lacquer is made from the sap of the urushi tree, also known as the lacquer tree or the Japanese varnish tree (Rhus vernacifera), which mainly grows in Japan and China, as well as Southeast Asia. Japanese lacquer, 漆 urushi, is made from the sap of the lacquer tree. The tree must be tapped carefully, as in its raw form the liquid is poisonous to the touch, and even breathing in the fumes can be dangerous. But people in Japan have been working with this material for many millennia, so there has been time to refine the technique!

Flowing from incisions made in the bark, the sap, or raw lacquer is a viscous greyish-white juice. The harvesting of the resin can only be done in very small quantities.

Three to five years after being harvested, the resin is treated to make an extremely resistant, honey-textured lacquer. After filtering, homogenization and dehydration, the sap becomes transparent and can be tinted in black, red, yellow, green or brown.

Once applied on an object, lacquer is dried under very precise conditions: a temperature between 25 and 30°C and a humidity level between 75 and 80%. Its harvesting and highly technical processing make urushi an expensive raw material applied in exceptionally fine successive layers, on objects such as bowls or boxes, or as you see, samurai sword saya {scabbards}. After heating and filtering, urushi can be applied directly to a solid, usually wooden, base. Pure urushi dries into a transparent film, while the more familiar black and red colours are created by adding minerals to the material. Each layer is left to dry and polished before the next layer is added. This process can be very time-consuming and labour-intensive, which contributes to the desirability, and high costs, of traditionally made lacquer goods. The skills and techniques of Japanese lacquer have been passed down through the generations for many centuries. For four hundred years, the master artisans of Zohiko’s Kyoto workshop have provided refined lacquer articles for the imperial household. It is extraordinary that a finest urushi lacquer saya would have taken up to, and over, a year to hand produce, by some of the most finely skilled artisans in the world.

Shakudo {that can be used to make samurai sword mounts and fittings} is a billon of gold and copper (typically 4-10% gold, 96-90% copper) which can be treated to form an indigo/black patina resembling lacquer. Unpatinated shakudo Visually resembles bronze; the dark colour is induced by applying and heating rokusho, a special patination formula.

Shakudo was historically used in Japan to construct or decorate the finest katana fittings such as fuchi-kashira, tsuba, menuki, and kozuka; as well as other small ornaments. When it was introduced to the West in the mid-19th century, it was thought to be previously unknown outside Asia, but recent studies have suggested close similarities to certain decorative alloys used in ancient Egypt, Greece, and Rome.

The above descriptions show just why the finest Japanese fully mounted swords can be referred to as ‘Art Swords’, not because they were made just to be items of incredible beauty, to admire and revere, but also, as usable, everyday use swords to be worn by highest status samurai and clan lords, that are also statements of the status of the wearer, as well as of the finest beauty and artistic merit. The blade is absolutely beautiful, with just small elements of natural age surface thinning at the top quarter on one side.

“In these textures lies an extraordinary and unique feature of the sword - the steel itself possesses an intrinsic beauty. The Japanese sword has been appreciated as an art object since its perfection some time during the tenth century AD. Fine swords have been more highly prized than lands or riches, those of superior quality being handed down from generation to generation. In fact, many well-documented swords, whose blades are signed by their makers, survive from nearly a thousand years ago. Recognizable features of the blades of hundreds of schools of sword-making have been punctiliously recorded, and the study of the sword is a guide to the flow of Japanese history.”

Victor Harris

Curator, Assistant Keeper and then Keeper (1998-2003) of the Department of Japanese Antiquities at the British Museum. He studied from 1968-71 under Sato Kenzan, Tokyo National Museum and Society for the Preservation of Japanese Swords

As once told to us by an esteemed regular visitor to us here in our gallery, and the same words that are repeated in his book;

Blade 25 inches long tsuba to tip, overall in its saya, 33.6 inches long read more

7450.00 GBP