Japanese

Very Rare Circa 1700’s Japanese Nagasaki Emigre Sword Maker. A ‘Sawasa’ Naval Hanger A Japanese Hangar in The European Style, For a Senior Officer of the Dutch East India Company ( the VOC). A VOC Naval Captain of A So Called ‘Black Ship’

Made by Japanese emigre samurai sword koshirae makers and artisans, after 1639, by exiled Japanese sword fitting craftsmen working in Batavia, for a VOA Naval Admiral or Captain, likely a permitted trading black ship voyaging to the trading post at the Nagasaki island Dejima.

The Black Ships (in Japanese: 黒船, romanized: kurofune, Edo period term) were the names given to Portuguese and Dutch merchant ships,

In 1543, Portuguese initiated the first contacts, establishing a trade route linking Goa to Nagasaki. The large carracks engaged in this trade had the hull painted black with pitch, and the term came to represent all Western vessels. In 1639, after suppressing a rebellion blamed on the influence of Christian thought, the ruling Tokugawa shogunate retreated into an isolationist policy, the Sakoku. During this "locked state", contact with Japan by Westerners was restricted to Dutch traders on Dejima island at Nagasaki.

European hanger swords were the weapon of choice for senior maritime officers employed by the Dutch East India Company VOC , in fact by all senior naval officers at the time, including notorious pirates such as Edward Teach, aka ‘Blackbeard’. The hilt and fittings of this sword were probably added to the European blade by Japanese émigrés in the Dutch colony of Batavia (Jakarta).

They were made using the sawasa technique of gilded copper alloy with black shakudo detailing. Japanese samegawa grip {giant rayskin}, with a vertical panel, engraved with an exotic bird in front of two Indonesian mosque temple domes.

The level of workmanship suggests that the sword belonged to a high-ranking company official.

A fine and jolly rare Japanese export Sawasa hunting hanger. It features a straight blade with a double-edged tip and wide fuller, flanked by a narrow groove near the spine. In the base of the fuller on either side are a running stag and a boar, both prized hunting animals, and French motto of honour.

Sometimes referred to as 'Tonkinese chiseled work', these 18th century export wares became highly sought after, such as this 18th century Sawasa sword

The desiring incorporates a single shell-guard, chased and gilded in high relief against a blackened fish-roe shakudo ground, chisseled with reclining Eros with his bow and quiver. the hilt quilon block is chisseled on one sade by a collared hunting hound and tiger to the other side. The knuckle bow is chisseled with the figure of a turbanned Jakartan figure. the pommel is chisseled with a stag, and the quillon end is a stag hoof, and a covering in panels of Japanese samegawa {giant rayskin}. Overall the hilt is decorated with a combination of artistic styles of the Dutch East Indies, and Europe, made by Japanese emigre artistry with japanese samegawa binding, finished in a mixture of shakudo and gilt.

This sword is a beauty in a superb state of preservation.

Sawasa is the Japanese name given to objects made by Asian artisans, adopting European models combined with Japanese and Chinese materials and decorative motifs. This decoration consists of refined gilt relief and engraving on a lustrous lacquered surface. Sawasa wares are the result of cultural interaction between Asia and Europe. As a consequence of global trade in the 17th century, mutual interest arose in the peculiarities of each other’s culture. The Dutch and other Europeans brought rare objects back from their travels which whetted the appetite for exotic rarities. The earliest Sawasa objects are sword and hanger hilts and tobacco boxes ordered in Japan from Batavia, now Jakarta. Sawasa demonstrates not only the intercontinental commercial connections created by the Dutch East India Company (VOC) but also mutual cultural influences between Europe and Asia.

The decoration of the fittings are of the Japanese export style, in the European manner, but with fine and typical Japanese influences for a black ship naval captain of the VOC, in the late seventeenth or early eighteenth centuries, a style of metalwork known as sawasa that was produced for the Dutch East India Company in and around Nagasaki. Following Japan’s closed country (sakoku) edicts, from around 1639, exiled Japanese sword fitting craftsmen began working in Batavia, where the market for sawasa was a profitable one. The idea of sawasa was that objects made from a copper alloy were given gilt relief decoration with black lacquered highlights to achieve the appearance of shakudō. The extensive metalwork here resembles shakudō, but is likely to be sawasa with highlights in gold. The ground is covered with fine punch marks in a pattern resembling fish roe (nanako), although the punch marks are not completely uniform. The wooden hilt is covered on each side with panels of brass alloy, over Japanese samegawa giant ray skin and once overlaid with gold leaf;

Blade is engraved, on both sides, Ne me Tirez pas sans Raisons.. Ne me Remette point sans Honneur

Do not shoot me without reason do not hand me over without honour.

The hilt and blade is exceptionally sound and great condition, but with all the due appropriate age and surface wear from the past three hundred years

Picture in the gallery, a Japanese woodblock print, of a 17th century Dutch East India Co. vessel trading in Japan, a so-called Black Ship.

Another example of a Sawasa sword sold last May 24 for £14,080. It was a small sword, with an engraved blade. the engraving on that sword looks incredibly like it was created by the same hand as ours. Although the gilt on that small sword was mostly near perfect, where ours is not perfect.

For reference;

Sawasa – Japanese Export Art in Black and Gold 1650-1800 Rijksmuseum Amsterdam.

Every item is accompanied with our unique, Certificate of Authenticity. Of course any certificate of authenticity, given by even the best specialist dealers, in any field, all around the world, is simply a piece of paper,…however, ours is backed up with the fact we are the largest dealers of our kind in the world, with over 100 years and four generation’s of professional trading experience behind us.

See Bas Kist et al, Sawasa Japanese export art in black and gold 1650-1800, exhibition catalogue, Rijksmuseum Amsterdam, 28 November 1998 - 28 February 1999, pp. 53-54, A.13.1 - A.14.1 (illustrated)

For a related example formerly in the collection of the late A.R. Dufty F.S.A., past Master of the Armouries, H.M. Tower of London, see Christie's South Kensington, Antique Arms and Armour, 15 July 1998, lot 28 read more

2450.00 GBP

A Delightful & Beautiful Early to Mid Edo Period 1598-1863 Samurai War Arrow. A Long Bladed Armour Piercing Tagari-Ya, With Yadake Bamboo haft, & Sea Eagle Feather Flights and a Traditional Tamahagane Tempered Steel Head In Stunning Polish with Hamon

Yanagi-Ha (willow leaf) Form. With original traditional eagle feathers, probably the large edge-wing feathers of a Japanese sea eagle.

The armour pierceing arrow tip, of yanagi-ha form, that is swollen at the tip to have the extra piercing power to penetrate armour and helmets {kabuto}, is a brightly polished, traditional tamagahane steel hand made, by a sword smith, long arrow head, originally hand made with folding and tempering exactly as would be a samurai sword blade, possibly signed on the tang under the binding but we would never remove it to see. The Edo period early eagle feathers are now slightly worn.

It is entirely indicative of the Japanese principle that as much time skill and effort be used to create a single 'fire and forget' arrow, as would be used to make a tanto or katana. A British or European blacksmith might once have made ten or twenty arrows a day, a Japanese craftsman might take a week to make a single arrow, that has a useable combat life of maybe two minutes, the same as a simplest British long bow arrow.

The Togari-Ya or pointed arrowheads look like a miniature version of a long Yari (spear) and were used only for war and are armour piercing arrows . Despite being somewhat of a weapon that was 'fire and forget' it was created regardless of cost and time, like no other arrow ever was outside of Japan. For example, to create the arrow head alone, in the very same traditional way today, using tamahagane steel, folding and forging, water quench tempering, then followed by polishing, it would likely cost way in excess of a thousand pounds, that is if you could find a Japanese master sword smith today who would make one for you. Then would would need hafting, binding, and feathering, by a completely separate artisan, and finally, using eagle feathers as flights, would be very likely impossible. This is a simple example of how incredible value finest samurai weaponry can be, items that can be acquired from us that would cost many times the price of our original antiques in order to recreate today. Kyu Jutsu is the art of Japanese archery.The beginning of archery in Japan is pre-historical. The first images picturing the distinct Japanese asymmetrical longbow are from the Yayoi period (c. 500 BC – 300 AD).

The changing of society and the military class (samurai) taking power at the end of the first millennium created a requirement for education in archery. This led to the birth of the first kyujutsu ryūha (style), the Henmi-ryū, founded by Henmi Kiyomitsu in the 12th century. The Takeda-ryū and the mounted archery school Ogasawara-ryū were later founded by his descendants. The need for archers grew dramatically during the Genpei War (1180–1185) and as a result the founder of the Ogasawara-ryū (Ogasawara Nagakiyo), began teaching yabusame (mounted archery) In the twelfth and thirteenth century a bow was the primary weapon of a warrior on the battlefield. Bow on the battlefield stopped dominating only after the appearance of firearm.The beginning of archery in Japan is pre-historical. The first images picturing the distinct Japanese asymmetrical longbow are from the Yayoi period (c. 500 BC – 300 AD).

The changing of society and the military class (samurai) taking power at the end of the first millennium created a requirement for education in archery. This led to the birth of the first kyujutsu ryūha (style), the Henmi-ryū, founded by Henmi Kiyomitsu in the 12th century. The Takeda-ryū and the mounted archery school Ogasawara-ryū were later founded by his descendants. The need for archers grew dramatically during the Genpei War (1180–1185) and as a result the founder of the Ogasawara-ryū (Ogasawara Nagakiyo), began teaching yabusame (mounted archery) Warriors practiced several types of archery, according to changes in weaponry and the role of the military in different periods. Mounted archery, also known as military archery, was the most prized of warrior skills and was practiced consistently by professional soldiers from the outset in Japan. Different procedures were followed that distinguished archery intended as warrior training from contests or religious practices in which form and formality were of primary importance. Civil archery entailed shooting from a standing position, and emphasis was placed upon form rather than meeting a target accurately. By far the most common type of archery in Japan, civil or civilian archery contests did not provide sufficient preparation for battle, and remained largely ceremonial. By contrast, military training entailed mounted maneuvers in which infantry troops with bow and arrow supported equestrian archers.

Mock battles were staged, sometimes as a show of force to dissuade enemy forces from attacking. While early medieval warfare often began with a formalized archery contest between commanders, deployment of firearms and the constant warfare of the 15th and 16th centuries ultimately led to the decline of archery in battle. In the Edo period archery was considered an art, and members of the warrior classes participated in archery contests that venerated this technique as the most favoured weapon of the samurai. In the gallery is from an edo exhibition of archery that shows a tagari ya arrow pierced completely through, back and front, an armoured steel multi plate kabuto helmet.

Every item is accompanied with our unique, Certificate of Authenticity. Of course any certificate of authenticity, given by even the best specialist dealers, in any field, all around the world, is simply a piece of paper,…however, ours is backed up with the fact we are the largest dealers of our kind in the world, with over 100 years and four generation’s of professional trading experience behind us read more

645.00 GBP

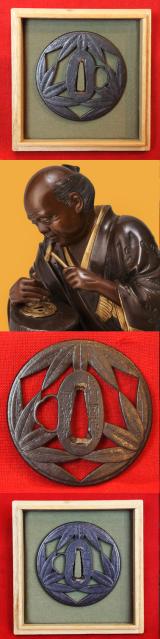

Superb Tsuba Signed Choshu Koku Hagi ju Kawaji Go {no} Ju Tomochika. A Retainer of The Mori Daimyo

The westerly province of Chōshū (Nagato) was the home of eight or more important families engaged in making sword-furniture, of whom the parent was the Nakai group, originally established in the neighbouring province of Suō. The indication “of Hagi” (Hagi no jū), so frequently added to the signatures on Chōshū work, may not perhaps in all cases imply the artist’s actual residence at the Nagato capital.

The early work was influenced by Umetada Miōju (Group XI), who spent some time at the Suō capital, Yamaguchi, as well as by members of the Shōami group (XII); thus, examples by the Nakai often show incrustation of the softer metals on the iron ground. Chōshū guards are usually in iron of a rich black patina, with sharp, powerful and carefully modelled relief, either solid or perforated. There may be a sparing enrichment of gold, but this is unusual.

After the Tokugawa family had reconstituted Japan’s central government in 1603, the head of the Mōri family became the daimyo, or feudal lord, of Chōshū, the han (fief) that encompassed most of the western Honshu region. Although the Tokugawa tolerated the existence of the Mōri in Chōshū, the two clans remained hostile toward each other. Chōshū warriors played the leading role in the overthrow of the Tokugawa government in 1867, after which Chōshū men dominated the new government until the end of World War II. Nevertheless, throughout the Tokugawa period (1603–1867) the Mōri family indoctrinated their warriors with hatred of the Tokugawa family and respect for the emperor, whose power the Tokugawa usurped. When Chōshū warriors led the fight to overthrow the Tokugawa in 1867, they did so under the banner of restoring power to the emperor.

74mm read more

995.00 GBP

A Very Impressive, Attractive, & Massive, Sukashi, Japanese Yanone {Arrow} Yanagi-Ba (Willow Leaf) With Long Tang. With Pierced Boar's Eye and Flower Head Clan Mon Likely a Presentation Piece

A beautiful very large arrow head {Ya} in nice polish, showing just a few tiny age marks. We can see it was re-polished some years ago. Likely Edo era.

Yanagi-Ba (Willow Leaf)

Yanone are very elaborate with saw-cut patterns like Sakura (cherry blossom), Inome (heart shape or boars eye), Mon patterns (family crests), dragons ad other geometrical patterns. These arrowheads are usually signed on the blade below the piercing and above the shoulder. Normally there are characters on both sides of the blade but in many cases the signature (mei) has been almost polished away.

This style of arrowhead appeared during the Momoyama period (1573-1615) and continued through the relatively peaceful Edo Period

The Togari-Ya or pointed arrowheads look like a small Yari (spear) and were used only for war and are armour piercing arrows . Despite being somewhat of a weapon that was 'fire and forget' it was created regardless of cost and time, like no other arrow ever was outside of Japan. For example, to create the arrow head alone, in the very same traditional way today, using tamahagane steel, folding and forging, water quench tempering, then followed by polishing, it would likely cost way in excess of a thousand pounds, that is if you could find a Japanese master sword smith today who would make one for you. Then would would need hafting, binding, and feathering, by a completely separate artisan, and finally, using eagle feathers as flights, would be very likely impossible. This is a simple example of how incredible value finest samurai weaponry can be, items that can be acquired from us that would cost many times the price of our original antiques in order to recreate today. Kyu Jutsu is the art of Japanese archery.The beginning of archery in Japan is pre-historical. The first images picturing the distinct Japanese asymmetrical longbow are from the Yayoi period (c. 500 BC – 300 AD).

The changing of society and the military class (samurai) taking power at the end of the first millennium created a requirement for education in archery. This led to the birth of the first kyujutsu ryūha (style), the Henmi-ryū, founded by Henmi Kiyomitsu in the 12th century. The Takeda-ryū and the mounted archery school Ogasawara-ryū were later founded by his descendants. The need for archers grew dramatically during the Genpei War (1180–1185) and as a result the founder of the Ogasawara-ryū (Ogasawara Nagakiyo), began teaching yabusame (mounted archery) In the twelfth and thirteenth century a bow was the primary weapon of a warrior on the battlefield. Bow on the battlefield stopped dominating only after the appearance of firearm.The beginning of archery in Japan is pre-historical. The first images picturing the distinct Japanese asymmetrical longbow are from the Yayoi period (c. 500 BC – 300 AD).

The changing of society and the military class (samurai) taking power at the end of the first millennium created a requirement for education in archery. This led to the birth of the first kyujutsu ryūha (style), the Henmi-ryū, founded by Henmi Kiyomitsu in the 12th century. The Takeda-ryū and the mounted archery school Ogasawara-ryū were later founded by his descendants. The need for archers grew dramatically during the Genpei War (1180–1185) and as a result the founder of the Ogasawara-ryū (Ogasawara Nagakiyo), began teaching yabusame (mounted archery) Warriors practiced several types of archery, according to changes in weaponry and the role of the military in different periods. Mounted archery, also known as military archery, was the most prized of warrior skills and was practiced consistently by professional soldiers from the outset in Japan. Different procedures were followed that distinguished archery intended as warrior training from contests or religious practices in which form and formality were of primary importance. Civil archery entailed shooting from a standing position, and emphasis was placed upon form rather than meeting a target accurately. By far the most common type of archery in Japan, civil or civilian archery contests did not provide sufficient preparation for battle, and remained largely ceremonial. By contrast, military training entailed mounted maneuvers in which infantry troops with bow and arrow supported equestrian archers. Mock battles were staged, sometimes as a show of force to dissuade enemy forces from attacking. While early medieval warfare often began with a formalized archery contest between commanders, deployment of firearms and the constant warfare of the 15th and 16th centuries ultimately led to the decline of archery in battle. In the Edo period archery was considered an art, and members of the warrior classes participated in archery contests that venerated this technique as the most favoured weapon of the samurai.

One of the photos in the gallery shows how arrow heads are often displayed in Japanese museums.

Weight 201 grams, 25 inches long overall, head 5.5 inches long, 2.3 inches wide read more

445.00 GBP

A Beautiful Edo Period Akasaka School O Sukashi Tsuba Decorated in Cut Silhouette With Clouds, Stars and Moon.

Early in the 17th century, tradition says, a dealer of Kiōto, named Kariganeya Hikobei, practised the designing of openwork iron guards in a new and refined style and had them made by a group of skilled craftsmen. From among these men he selected one Shōgunal capital, and settled with him at Kurokawa-dani in the Akasaka Japanese text district. Shōzayemon took the name of Tadamasa and continued his work on Kariganeya’s designs, dying in 1657. His son (or younger brother) Shōyemon, who succeeded him, calling himself Tadamasa II and adopting Akasaka as a surname, died in 1677 and was in turn succeeded by his son Masatora (d. 1707), by Masatora’s son Tadamune, and thence by four generations all called Tadatoki, the last living on into the middle of the 19th century. The first Tadatoki seems to have removed to Kiōto with his father’s pupil Tadashige and there to have founded a western branch of the school. Besides these a number of pupils, all called Tada-…, are recorded.

The earlier Akasaka guards closely resemble the pierced work of the Heianjō and Owari workers (Group III). Later productions display a number of striking features, such as clean-cut fret-piercing in positive silhouette of designs leaving little of the iron in reserve, the addition of a slight engraving finish, a rounded or rather tapered edge to the guard, and, in some of the more recent specimens, the semi-circular enlargement of each end of the tang-hole, as if to take a plug (not supplied) of abnormal size. Enrichments of other metals are entirely absent. read more

495.00 GBP

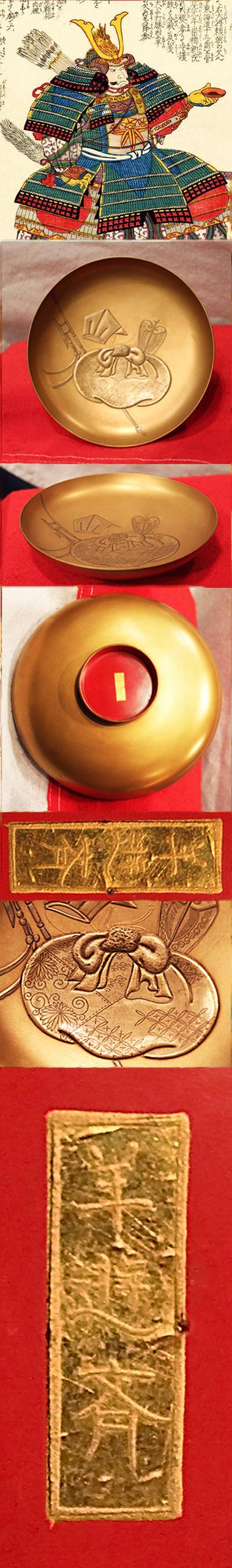

A Simply Fabulous Samurai's Loyalty, Ritual-Exchange, Wine Bowl, A Sakazuki of Hiramaki-e Pure Gold Lacquer. Signed Yoyusai (1772-1845)

A Sakazuki cup, a footed Circular Wine Cup of pure gold lacquer signed Hira Yoyusai decorated with the symbols of the highest ranking samurai, an Imperial court cap, a pole arm and General's war fan. Sakazuki is a ritual of exchanging sake cups as a means of pledging loyalty. The word itself refers to ceremonial cups used on special occasions like weddings, tea ceremonies, etc. There are currently two known versions of the sakazuki ritual.

Worthy of any museum grade collection of the finest Japanese Ob'ject D'art. Edo period (19th century), signed Yoyusai (1772-1845). A footed, circular cup of pure gold lacquer in gold hiramaki-e on fundame ground. Decorated with an Imperial court cap, a war fan, a pole arm and a tied sack. Likely commissioned for a notable of the highest rank, such as a daimyo lord or member of the Japanese nobility. In the period Kwansei, 1789 to 1801 C.E., Koma Kwansai, Inouye Hakusai, and Hara Yoyusai were the most famous artists, the first of whom was foremost in the delicacy of his work, but was comparatively unknown. Nakayama Komin was a distinguished lacquerer who worked in Edo and learnt the art from Hara Yoyusai (1772-1845). Yoyusai and other 19th-century lacquer artists including Koma Kansai and Zeshin, Nakayama Komin turned to famous early masterpieces of Japanese lacquer for inspiration. A superbly executed piece of finest artwork, showing remarkable skill for the minutest detail. Hiramaki-e, in Japanese lacquerwork, gold decoration in low, or flat, relief, a basic form of maki-e. The pattern is first outlined on a sheet of paper with brush and ink. It is then traced on the reverse side of the paper with a mixture of heated wet lacquer and (usually red) pigment. The artist transfers the pattern directly to the desired surface by rubbing with the fingertips, a process called okime. In the next step (jigaki), the pattern that has been transferred is painted over with lacquer usually a reddish colour. A dusting tube is used to sprinkle gold powder on the painted design while the lacquer is still wet. When the lacquer is dry, superfluous gold powder is dusted off, and a layer of clear lacquer is applied over the gold-covered design. When dry, it is polished with powdered charcoal. A second layer of lacquer is added, allowed to dry, and given a fingertip polish with a mixture of linseed oil and finely powdered mudstone.

The hiramaki-e technique, which dates from the latter part of the Heian period (794-1185), was preceded by togidashi maki-e, a technique in which not only the design but the whole surface is covered with clear lacquer after the sprinkling of metal powder; the lacquer is then polished down to reveal the design. During the Kamakura (1192-1333) and Muromachi (1338-1573) periods, hiramaki-e tended to be overshadowed by takamaki-e (gold or silver decoration in bold relief). It came fully into its own only in comparatively modern times. During the Azuchi-Momoyama period (1574-1600), hiramaki-e artists often left the sprinkled gold powder unpolished in a technique called maki-hanashi (left as sprinkled). A very beautiful piece by the master or an homage to Yoyusai bearing his name.

5" diameter across 1.33 inches high

Every single item from The Lanes Armoury is accompanied by our unique Certificate of Authenticity. Part of our continued dedication to maintain the standards forged by us over the past 100 years of our family’s trading, as Britain’s oldest established, and favourite, armoury and gallery read more

4950.00 GBP

A Very Attractive & Good Edo Period Antique Nanban Tsuba in Tetsu and Applied Gold

The style of decoration that involves a mass of tendrils occupied by dragons, with elongated oval seppa dai decorated with waves or bars and the like. Unusually the pierced design travels around the edge as well, a very nice sign of extra fine quality workmanship, and beautiful undercutting.

Nanban often regarded as meaning Southern Barbarian, are very much of the Chinese influence. The Chinese influence on this group of tsuba was of more import than the Western one, however, and resulted not merely in the utilisation of fresh images by the existing schools, but also in the introduction of a

completely fresh style of metalworking.

The term 'namban' was also used by the Japanese to describe an iron of foreign origin.

Neither can the Namban group be considered to represent 'native Japanese art'.

The required presence in the group, by definition, of 'foreign influence', together with the possibility of their being 'foreign made', was probably responsible for their great popularity at the time.

Tsuba are usually finely decorated, and are highly desirable collectors' items in their own right. Tsuba were made by whole dynasties of craftsmen whose only craft was making tsuba. They were usually lavishly decorated. In addition to being collectors items, they were often used as heirlooms, passed from one generation to the next. Japanese families with samurai roots sometimes have their family crest (mon) crafted onto a tsuba. Tsuba can be found in a variety of metals and alloys, including iron, steel, brass, copper and shakudo. In a duel, two participants may lock their katana together at the point of the tsuba and push, trying to gain a better position from which to strike the other down. read more

425.00 GBP

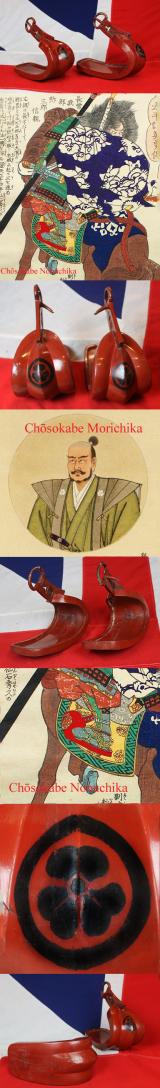

A Superb Pair of Red Lacquer Over Steel Abumi, Samurai Stirrups, Edo Period Used by Daimyo or Seieibushi (Elite Samurai) Traditionally the Highest Rank of Elite Samurai of The Sakai Clan,

Simply stunning pieces of antique samurai armour, perfect for the collector of samurai swords, armour and artifacts, or simply as fabulous object d'art, they would be spectacular decorative pieces in any setting, albeit to compliment contemporary minimalistic or fine antique decor of any period, oriental or European.

Decorated at the front with a beautiful kamon samurai clan crest of the renown samurai it's one of popular kamon that is a design of the flower of oxalis corniculata.

The founder of the clan that chose this flower as their mon had wished that their descendants would flourish well. Because oxalis corniculata is renown, and fertile plant.

the mon form as used by clans such as the Sakai, including daimyo lord Sakai Tadayo

One of the great Sakai clan lords was Sakai Tadayo (酒井 忠世, July 14, 1572 – April 24, 1636). He was a Japanese daimyō of the Sengoku period, and high-ranking government advisor, holding the title of Rōjū, and later Tairō.

The son of Sakai Shigetada, Tadayo was born in Nishio, Mikawa Province; his childhood name was Manchiyo. He became a trusted elder (rōjū) in Toyotomi Hideyoshi's government, alongside Tokugawa Ieyasu. Under Hideyoshi, he was made lord of Kawagoe Castle (in Musashi Province, today Saitama Prefecture) and later of Nagoya Castle in Kyūshū's Hizen Province. In 1600, in the lead-up to the decisive Sekigahara campaign, he fought against the Tokugawa at Aizu, and submitted to them at the siege of Ueda. Thus, having joined the Tokugawa prior to the battle of Sekigahara itself, Sakai was made a fudai daimyō, and counted among the Tokugawa's more trusted retainers. He served under Ieyasu for a time, and under the second shōgun, Tokugawa Hidetada, as a hatamoto.

The lacquered iron menpo (face mask) with four-lame yodarekake face armour. The kabuto is signed on the interior Nobutada saku Nobutada made this

During the Japanese civil wars (1467-1568), red was revered by the samurai and worn as a symbol of strength and power in battle, in ancient times it was a lacquer called sekishitsu (a mixture of cinnabar and lacquer). For example it was the trademark colour of the armour of the Li clan, the so called Red Devil’s. In the Battle of Komaki Nagakute, fought in 1584, Ii Naomasa's clan fronted 3,000 matchlock gunmen, his front line forces up wearing what would become the clan’s trademark, bright red lacquered armour, with high horn-like helmet crests. Their fearsome fighting skills with the gun and long-spear, and their red armour had them become known as Ii’s Red Devils. He fought so well at Nagakute, that he was highly praised by Toyotomi Hideyoshi leader of the opposition! Ii Naomasa was known as one of the Four Guardians of the Tokugawa.

Also the similar clan mon of the Chōsokabe clan (長 宗 我 部 氏Chōsokabe-shi ), Also known as Chōsokame (長 曾 我 部 、 長 宗 我 部 ) , Was a Japanese clan from the island of Shikoku . Over time, they were known to serve the Hosokawa clan then the Miyoshi clan, and then the Ichijō clan although they were later liberated and came to dominate the entire island, before being defeated by Toyotomi Hideyoshi . The clan claimed to be descendants of Qin Shi Huang (d. 210 BC), the first emperor of a unified China .

The clan is associated with the province of Tosa in present-day Kōchi prefecture on the island of Shikoku . Chōsokabe Motochika , who unified Shikoku, was the first twenty daimyo (or head) of the clan.

In the beginning of the Sengoku period , Chōsokabe Kunichika's father, Kanetsugu, was assassinated by the Motoyama clan in 1508. Therefore, Kunichika was raised by the aristocrat Ichijō Husaie of the Ichijō clan in Tosa province. Later, towards the end of his life, Kunichika avenged the Motoyama clan and destroyed with the help of Ichijō in 1560. Kunichika have children, including his heir and future daimyo of Chosokabe, Motochika, who continue unifying Shikoku.

First, the Ichijō family was overthrown by Motochika in 1574. Later, he gained control of the rest of Tosa due to his victory at the Battle of Watarigawa in 1575. Then he also destroyed the Kono clan and the Soga clan . Over the next decade, he extended his power to all of Shikoku in 1583. However, in 1585, Toyotomi Hideyoshi ( Oda Nobunaga's successor ) invaded the island with a force of 100,000 men, led by Ukita Hideie , Kobayakawa Takakage , Kikkawa Motonaga , Toyotomi Hidenaga and Toyotomi Hidetsugu . Motochika surrendered and lost the Awa provinces, Sanuki and Iyo ; Hideyoshi allowed him to retain Tosa. The smiths name Motochika was linked to the clan itself. The last picture In the gallery is of samurai Chōsokabe Morichika, ruler of Tosa province. His clan mon, that appears on the abumi and on the tanto on the habaki, can be seen on the collar of his garb, As ruler of Tosa Province, in 1614 he went to join the defenders of Osaka Castle against the Tokugawa, he arriving there the same day as Sanada Yukimura. His Chōsokabe contingent fought very well in both the Winter and Summer at Osaka Campaigns. After the fall of Osaka, Morichika attempted to flee but was apprehended at Hachiman-yama by Hachisuka men, He and his sons were beheaded on May 11, 1615, following the defeat of the Toyotomi and Chōsokabe forces at the Battle of Tennōji. We acquired these abumi with tanto of the 1390's of the same clan, but sold separately.

These abumi are in superb condition for their age, certainly showing signs of use on horseback, but these slight wear marks etc. perfectly compliment their provenance for display. read more

3750.00 GBP

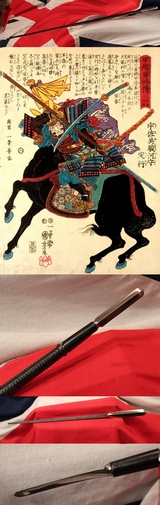

An Edo Period, 1603 - 1868, Samurai Horseman’s Ryo-Shinogi Yari Polearm

With original pole and iron foot mount ishizuki. Very nicely polished four sided double edged head. The mochi-yari, or "held spear", is a rather generic term for the shorter Japanese spear. It was especially useful to mounted Samurai. In mounted use, the spear was generally held with the right hand and the spear was pointed across the saddle to the soldiers left front corner. The warrior's saddle was often specially designed with a hinged spear rest (yari-hasami) to help steady and control the spear's motion. The mochi-yari could also easily be used on foot and is known to have been used in castle defense. The martial art of wielding the yari is called sojutsu. A yari on it's pole can range in length from one metre to upwards of six metres (3.3 to 20 feet). The longer hafted versions were called omi no yari while shorter ones were known as mochi yari or tae yari. The longest hafted versions were carried by foot troops (ashigaru), while samurai usually carried a shorter hafted yari. Yari are believed to have been derived from Chinese spears, and while they were present in early Japan's history they did not become popular until the thirteenth century.The original warfare of the bushi was not a thing for "commoners"; it was a ritualized combat usually between two warriors who may challenge each other via horseback archery and sword duels. However, the attempted Mongol invasions of Japan in 1274 and 1281 changed Japanese weaponry and warfare. The Mongol-employed Chinese and Korean footmen wielded long pikes, fought in tight formation, and moved in large units to stave off cavalry. Polearms (including naginata and yari) were of much greater military use than swords, due to their much greater range, their lesser weight per unit length (though overall a polearm would be fairly hefty), and their great piercing ability. Swords in a full battle situation were therefore relegated to emergency sidearm status from the Heian through the Muromachi periods. The pole has has the top lacquer section relacquered in the past 50 years or so. read more

2150.00 GBP

A Very Attractive, Edo Era 17th to 18th Century Samurai's Tetsu Abumi Stirrup, Inlaid With Silver in a Geometric Pattern

This Japanese stirrup, is made in the traditional dove's breast (hato mune) shape with an open platform lined slightly curved forward so that the foot fits in without sliding backwards. In the front extremity the stirrup has a rectangular buckle with several horizontal slots which also serve as a handle.

The whole surface is in ancient russetted iron in the distinctive Higo school style, with a large onlaid decorative mount of a bird and various flora.

It is to be noted that these stirrups, due to their weight, were also used as weapons against the infantry adversaries. Abumi, Japanese stirrups, were used in Japan as early as the 5th century, and were a necessary component along with the Japanese saddle (kura) for the use of horses in warfare. Abumi became the type of stirrup used by the samurai class of feudal Japan Early abumi were flat-bottomed rings of metal-covered wood, similar to European stirrups. The earliest known examples were excavated from tombs. Cup-shaped stirrups (tsubo abumi) that enclosed the front half of the rider's foot eventually replaced the earlier design.

During the Nara period, the base of the stirrup which supported the rider's sole was elongated past the toe cup. This half-tongued style of stirrup (hanshita abumi) remained in use until the late Heian period (794 to 1185) when a new stirrup was developed. The fukuro abumi or musashi abumi had a base that extended the full length of the rider's foot and the right and left sides of the toe cup were removed. The open sides were designed to prevent the rider from catching a foot in the stirrup and being dragged.

The military version of this open-sided stirrup, called the shitanaga abumi, was in use by the middle Heian period. It was thinner, had a deeper toe pocket and an even longer and flatter foot shelf. It is not known why the Japanese developed this unique style of stirrup, but this stirrup stayed in use until European style-stirrups were introduced in the late 19th century. The abumi has a distinctive swan-like shape, curved up and backward at the front so as to bring the loop for the leather strap over the instep and achieve a correct balance. Most of the surviving specimens from this period are made entirely of iron, inlaid with designs of silver or other materials, and covered with lacquer. In some cases, there is an iron rod from the loop to the footplate near the heel to prevent the foot from slipping out. The footplates are occasionally perforated to let out water when crossing rivers, and these types are called suiba abumi. There are also abumi with holes in the front forming sockets for a lance or banner. Seieibushi (Elite Samurai)

Traditionally the highest rank among the samurai, these are highly skilled fully-fledged samurai. Most samurai at the level of Seieibushi take on apprentices or Aonisaibushi-samurai as their disciples.

Kodenbushi (Legendary Samurai)

A highly coveted rank, and often seen as the highest attainable position, with the sole exception of the rank of Shogun. These are samurai of tremendous capability, and are regarded as being of Shogun-level. Kodenbushi are hired to accomplish some of the most dangerous international missions. Samurai of Kodenbushi rank are extremely rare, and there are no more than four in any given country.

Daimyo (Lords)

This title translates to 'Big Name' and is given to the heads of the clan.

Shogun (Military Dictator)

The apex of the samurai, the Shogun is the most prestigious rank possible for a samurai. Shoguns are the leaders of their given district, or country, and are regarded as the most powerful samurai. read more

1395.00 GBP